-

Services

-

Unified Patent Court (UPC) has started its operation on June 1, 2023. The UPC system simplifies patenting in Europe such that it is possible to request unitary effect for a granted European patent in countries, which have ratified the Agreement on a Unified Patent Court (UPCA) (17 EU member states at the moment). A European patent with unitary effect may also be referred to as a Unitary Patent (UP).

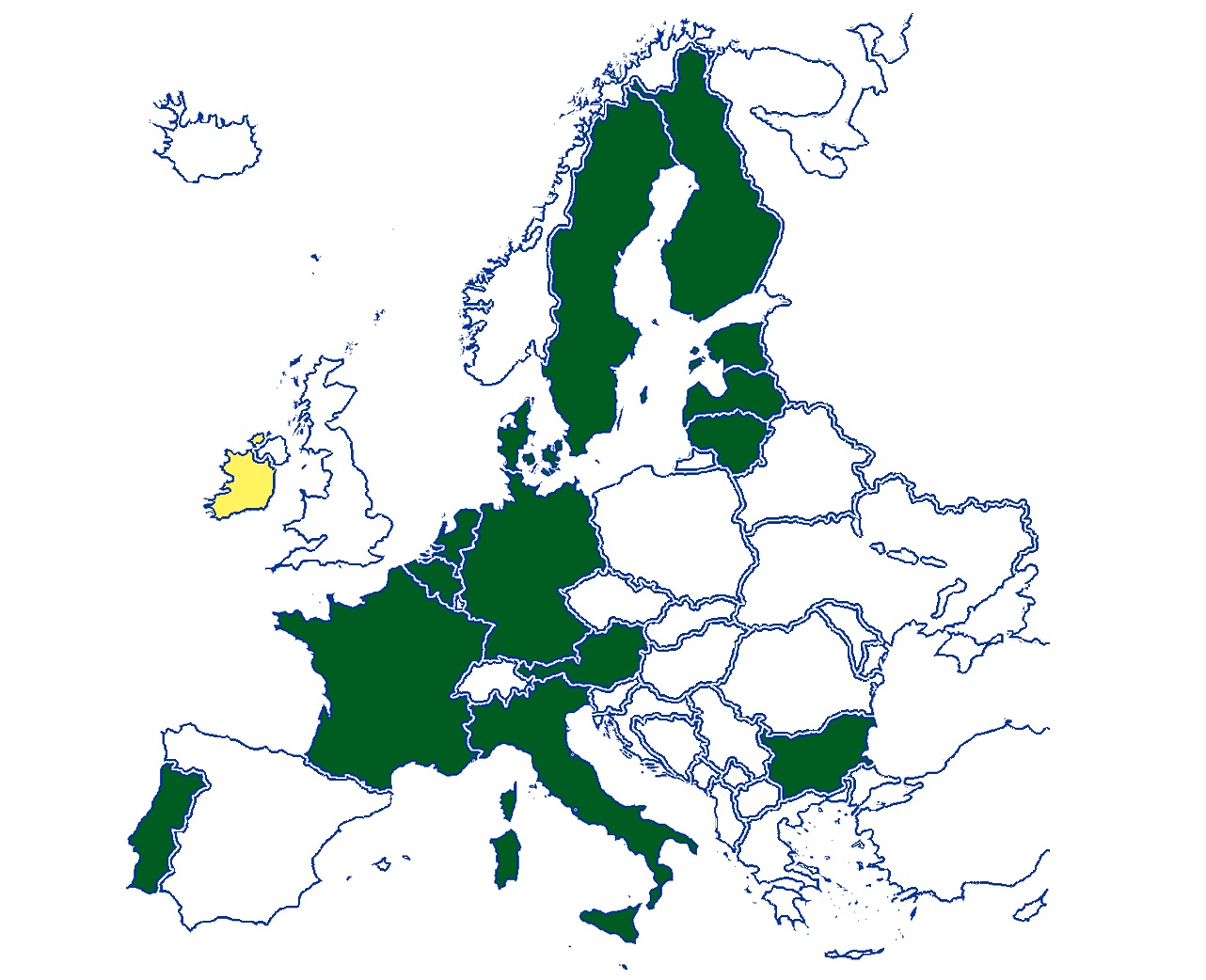

The countries which have ratified the UPCA are at the moment (marked with green in the map): Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia and Sweden.

The UPCA has been signed by 24 current EU member states, including Ireland. Ireland is not a Contracting Member State of the UPC yet though, because Ireland has not ratified the UPCA.

Ireland belongs to the European Patent Convention (EPC) anyway and has participated in the regulation of the UP. Consequently, Ireland may choose to ratify the UPCA and become a UPC Contracting Member State.

A referendum has to be arranged in Ireland before joining, because an amendment to the Constitution is required. The plan was to arrange the referendum in Ireland in June 2024, but the referendum has been deferred. According to Minister Burke, more time is needed for public discourse on the matter, but at least he remains committed to Ireland participating in the UPC and sees that it would bring many benefits for their economy.

We will continue to actively monitor the situation and get back to you as soon as we know more.

Original news can be found here.

We are honored to share that Laine IP has been recognized with the “Firm of the Year” award for Trademark Prosecution in Finland at this year’s Managing IP Awards. The award ceremony, held at the London Hilton on Park Lane, brought together the best of the intellectual property community from across the globe. Our expert Tom-Erik Hagelberg was present at the event and had the honor of accepting the award on behalf of our team.

In today’s digital age, where brand identity and online presence are invaluable assets, the significance of robust trademark protection cannot be overstated. It’s the foundation upon which businesses can build a strong, recognizable brand and safeguard their intellectual property from potential infringement. Our commitment to providing thorough and strategic trademark protection has always been at the forefront of our efforts.

This recognition is a reflection of the dedication and hard work of our entire team over the past year. From our attorneys to our administrative staff, every member of our trademark department has contributed tirelessly to our firm’s success. We’ve navigated challenges, celebrated achievements, and, most importantly, we’ve supported our clients through the complexities of intellectual property law with a steadfast commitment to excellence and integrity.

We also want to take a moment to extend our congratulations to all the nominees and winners of the night. Being among such esteemed company is truly an honor and speaks volumes of the vibrant and dedicated IP community we’re proud to be part of.

As we celebrate this achievement, our focus remains on the continuous improvement of our services and staying at the forefront of intellectual property law to better serve our clients. We believe in the power of teamwork, the importance of innovation, and the value of each trademark we protect and prosecute.

To our clients, thank you for entrusting us with the protection of your most valuable assets. Your trust fuels our commitment to excellence. We look forward to continuing to serve you with the dedication and quality that you deserve.

In the world of intellectual property law, Patent Agents play a pivotal role in safeguarding innovation and ensuring the legal protection of groundbreaking ideas. Becoming a successful Patent Agent requires a diverse set of skills and knowledge spanning legal, business and technical domains. None of the experts entering the profession has all the required skills to begin with and thus in-house training is an important part of the career path.

Laine IP is constantly looking for the best candidates for entering our training program. The training program is a mix of self-study, courses and practical work with real cases and clients. Candidates are closely mentored by an experienced Patent Attorney for several years to ensure that candidates feel confident in tackling all aspects of the profession.

We had a chat with two of our most recent U.S. Patent Agent trainees, Cristina Battistuzzi and Thomas Öhman, about their experiences working at Laine IP as trainees. Let’s see what they have to say about the training period.

Thomas: Before joining Laine IP in October 2023, I graduated in September 2023 with an M.Sc. in chemical engineering from Åbo Akademi University, majoring in Natural Materials Technology. I did not have any prior experience with IPR before joining.

Cristina: I have a M.S. in analytical chemistry from the University of Helsinki and a B.S. in Chemistry from a college in the US. My previous position here in Finland was at Thermo Fisher Scientific as part of the customer/quality control team. I have quite a varied background, I have research experience in the field of neuroscience while living in New York and teaching middle school science in Italy. I had no prior experience in IPR before joining Laine.

Thomas: I work in our Turku office, where only a couple of people from the firm work full-time. When I started, I travelled to our Helsinki office a few times a week to work more closely with my mentors Mark Scott and Toimi Teelahti, but now I go to Helsinki around once a week.

I usually arrive at the office between 10 and 11 a.m., after spending the first few hours of the day working at home by studying the material for the exam required for becoming an U.S. Patent Agent. Once at the office, I start looking at the relevant case assigned to me, and usually start drafting either a report for the client or a response to an office action. Other than that, I often communicate with Mark and Toimi and receive feedback for the work I’ve done, which is very valuable for my learning. We also have different team or company meetings at times, but most of the workday is spent working individually on a case.

Cristina: I enjoy a coffee and a chocolate and my day begins by checking assignments and discussing them with my mentor Mark Scott. In-between assignments, I follow the online course.

Thomas: I would say I learn about 50% from working on cases and 50% from studying the exam material. I’m currently in the process of completing an online study course which consists of modules with lectures and questions. I work on the study material independently for a few hours each day.

Most of the practical stuff is learned in the company’s actual cases, in which I learn, for example, to argue for patentability. Working on actual cases increases my knowledge of the patenting process as a whole, as the cases can be at any point of the patenting process, for example at the beginning, or nearing an actual patent. Together with Mark and Toimi, we regularly review both the practical work done as well as the material I’ve studied.

Cristina: The training is made up of studying for the Patent Bar Examination, and practical office work to assist the US Team in filing patent applications. As a study guide, we follow an online course based on the MPEP and in addition we have weekly meetings with Mark and Toimi who share their experience.

Thomas: I think some of the best parts are that we get to look at very different inventions, especially in the U.S team, as well as the feeling when you finally find a “break-through” in your arguments, that you believe could lead to a patent. Further, I like the flexible working times and the possibility to work at home.

Cristina: I enjoy problem solving and the continuous learning experience; there is no chance of being bored.

Thomas: Excellent written English, attention to detail, ability to communicate clearly, and the ability to learn and adapt after receiving feedback.

Cristina: You need to be a curious person, who enjoys learning, and gathering information from different sources and analyzing it in ways that are useful for communication with the US patent office as well as with the client. Patents are a whole new world if you have never worked with them before, so every day you need to be ready to put on your hiking shoes and go.

If you believe that you would make an excellent Patent Agent, please do not hesitate to contact us! Also have a look at our open position.

= A system spanning the European Union for the registration of trademarks at the EU Trademark Office, known as the EUIPO.

To apply for an EU trademark, an applicant must submit an application to the EUIPO. The EUIPO evaluates whether the trademark is distinct enough. Distinctiveness implies that the trademark should not directly describe the goods or services for which protection is sought. Instead, it must stand out from generic terms and abbreviations commonly used in the relevant industry. If a trademark fails to meet this criterion, the EUIPO will deny the application. However, before rejecting an application, the EUIPO issues a Notification of Refusal, giving the applicant an opportunity to contest the grounds for refusal with counterarguments.

Applicants must also specify the goods and services for which they seek trademark protection.

The EUIPO does not assess the similarity of the trademark to any previous registrations that may be identical or similar and registered for related goods or services. The responsibility to identify and challenge similar trademarks falls to the owners of existing trademarks. They must monitor the EUIPO’s publication of new trademarks and, if they find a potentially infringing trademark, file an opposition within three months after its publication in the EUIPO database. Oppositions can be filed by owners of earlier EU trademark registrations or national trademark registrations within any EU Member State. Additionally, any party can oppose a trademark on the basis of insufficient distinctiveness.

Distinctiveness: A trademark must distinguish the applicant’s goods and services from those of others and should not merely describe or be a generic term for the goods/services applied for. It is a fundamental requirement for trademark registration.

Classification: A classification system to identify the goods and/or services for which trademark protection is sought.

Office Action: A notification of refusal from the EUIPO, requiring a response from the applicant, usually regarding the application’s classification or the trademark’s distinctiveness.

Priority: Date of priority. The filing date of the first application concerning the mark, from which a six-month priority period is calculated. The applicant benefits from this period if they make a subsequent application for the same trademark outside the EU.

Opposition: A process to challenge the registration of a trademark by another party.

Application Fee: A fee associated with submitting a trademark application to the EUIPO. The application will not proceed if this fee is unpaid.

Opposition Fee: An official fee paid to the EUIPO by the party filing an opposition against a newly published EU trademark registration.

Renewal Fee: A fee for maintaining the trademark registration, payable to the EUIPO every ten years, with no limit on the number of renewals.

We are thrilled to announce that our firm has been recognized for its outstanding contributions in the IPR field, being shortlisted for the prestigious Managing IP Awards 2024 in several categories. This recognition underscores our dedication to excellence, innovation, and our clients’ success in Finland and beyond.

Our firm has been distinguished in the following categories for Finland:

Additionally, we are proud to announce that one of our esteemed attorneys, Reijo Kokko, has been shortlisted as Practitioner of the Year for his remarkable contributions to trademark law. His dedication and expertise have not only benefited our clients but have also set a high standard in the IP law practice.

Read more about the shortlists here.

The Managing IP Awards program, now in its 19th year, celebrates significant achievements and developments in intellectual property over the last year, covering more than 50 jurisdictions and several IP practice areas. The winners will be revealed at a gala dinner hosted at the London Hilton on Park Lane on April 11, 2024.

As we await the announcement of the winners, we extend our heartfelt congratulations to all the shortlisted firms, companies, and individuals. Our firm’s recognition is a testament to our team’s hard work, expertise, and commitment to excellence in the ever-evolving field of IP law.

Stay tuned for more updates, and wish us luck as we look forward to the ceremony in London!

Unified Patent Court (UPC) has started its operation on June 1, 2023. The UPC system simplifies patenting in Europe such that it is possible to request for unitary effect for a granted European patent in the countries, which have ratified the Agreement on a Unified Patent Court (UPCA) (17 EU member states at the moment). A European patent with unitary effect may also be referred to as a Unitary Patent (UP).

The countries which have ratified the UPCA are at the moment (marked with green in the map): Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia and Sweden.

The UPCA has been signed by 24 current EU member states, including Ireland. Ireland is not a Contracting Member State of the UPC yet though, because Ireland has not ratified the UPCA.

Ireland belongs to the European Patent Convention (EPC) anyway and has participated in the regulation of the UP. Consequently, Ireland may choose to ratify the UPCA and become a UPC Contracting Member State.

A referendum has to be arranged in Ireland before joining, because an amendment to the Constitution is required. According to our latest information, the referendum will be arranged in June 2024, so we look forward to seeing if Ireland makes progress towards the UPC.

We will continue to actively monitor the situation and get back to you as soon as we know more.

Original news can be found here.

We are thrilled to announce that Laine IP has been elevated to the prestigious Silver-category in the latest World Trademark Review 1000 (WTR 1000) rankings for 2024. This promotion is a testament to our unwavering commitment to delivering exceptional trademark services and exceeding the expectations of our clients.

In the latest review, our clients have praised our team’s ability to understand and maintain the overall brand strategy, ensuring the effective management and elevation of the value of intellectual property assets. They have commended us for our swift approach, likening our team to in-house counsel, which they find extremely beneficial.

Heading our trademark team, Reijo Kokko has been recognized for his brilliant grasp of legal and business needs, offering holistic brand strategy with to-the-point and actionable advice. Joose Kilpimaa, overseeing the management and protection of global brand portfolios, has been lauded for his expertise in handling opposition proceedings and raising IP awareness. Our expert Tom-Erik Hagelberg plays a crucial role in building and implementing trademark strategies, further solidifying our team’s expertise and dedication to our clients’ success. Moreover, our clients have emphasized the importance of practitioners like Joose and Tom-Erik in educating and identifying the best ways to protect IP rights in a cost-effective manner.

We are also extremely grateful to all of our clients and partners, whose continual trust and support have been an essential part of our success in securing this promotion to the Silver-category in the WTR 1000 rankings. Furthermore, we are happy and honored to be recognized among the world’s leading trademark professionals and firms, and we remain committed to providing strategic solutions that empower our clients to protect and maximize the value of their intellectual property assets also in the future.

The office action you have received contains a negative opinion on your patent application, stating that the independent claims are already disclosed in the prior art. The publication referred to in the office action does indeed appear to contain all the features of the independent claims. How unfortunate! Should we raise a white flag at this stage and abandon the application? In most cases, no.

The Examiner uses the independent claims as a starting point for the examination because they define the scope of protection of the invention in its broadest form. The patent attorney tries to draft an independent claim in such a way that it has at least one distinguishing feature over the prior art. Nevertheless, as it is not desirable to limit the scope of protection of an invention unnecessarily, it is advisable to avoid adding excessive distinguishing features to an independent claim when drafting claims.

However, when drafting a patent application, it is practically impossible to be aware of all the material constituting the state of the art and it is therefore advisable to be prepared in advance for the possibility that the Examiner will probably find publications which were not known by the patent attorney when the patent application was drafted. Moreover, once filed, no new content can be added to the patent application, which poses its own challenges in overcoming the objections to patentability.

When drafting a patent application, potential obstacles to patentability are anticipated by creating so-called fallback positions, which can be used if it appears that the obstacles identified by the Office cannot be overcome without limiting the scope of protection of the independent claims. The most common form of fallback positions are therefore dependent claims.

In addition to the obstacles regarding patentability, the office action may also indicate which claims are new. If the novelty assessment in the office action is correct, and one of the dependent claims considered to be novel contains a feature or features which, when added to an independent claim, do not excessively limit the scope of protection, it is worth considering limiting the independent claim to such feature or features.

As a general practice, the drafted independent claim contains all the features necessary for the invention, and the optional features of the various embodiments of the invention will be the fallback positions in the dependent claims. In addition, it is possible to include in the specification of the patent application, separately, advantageous embodiments which may be later useful in limiting the independent claims.

When preparing fallback positions, it is good to take care that the dependent claims are not too narrow, which could unacceptably reduce the scope of protection of the invention. The ideal fallback position limits the scope of protection only to what is needed to distinguish the independent claim from the prior art and to make the independent claim inventive. On the other hand, scattering obvious features as dependent claims may not be the most effective way to ensure patentability. Often, a feature of an invention has, in addition to its broadest form, several narrower forms, each of which provides some additional advantage (which advantageously is also disclosed in the application), and such narrower forms are typically presented as preferred embodiments. Of these preferred embodiments, the most appropriate may be used as a limiting feature if the fallback position of the broadest scope of protection is not enough to provide a sufficient difference to the state of art. However, when limiting the scope of the claims, it should be noted that if two different features are limited, some Offices may require that all the limitations selected must be from the same so-called preference level.

Applicants from an EPC contracting state not having English, French or German as an official language can, in certain conditions, benefit from a reduction of some fees.

Presently, for example a Finnish applicant that is a small or medium-sized enterprise (according to a definition by the EU), a natural person, a non-profit organisation, a university or a public research organisation (a so called R.6(4)-entity) can benefit from a 30 % reduction from the examination fee when the request for examination is made in Finnish. This is a significant advantage in that the applicant does not need to do anything else than declare themselves to be a R.6(4)-entity and to add one phrase in Finnish to the request for grant form. The filing fee is also reduced, if the application is filed in Finnish, but the fee reduction is significantly smaller than the cost for translation.

The current language reduction applies also after 1.4.2024, but additionally all applicants that are R.6(4)-entities, except SME’s, can benefit from a reduction of some further fees, i.e. without any requirement as to the language or the place of business or residence. Applicants can also benefit from both reductions.

The reduction remains 30 %, and in addition to the filing and examination fee, it is available for the search, designation, grant and renewal fees.

Microenterprises have been added to the list of possible beneficiaries of the fee reductions, meaning enterprises employing fewer than 10 persons and having a turnover or balance sheet sum not exceeding 2 MEUR. Such companies have also previously been eligible for the language reductions, as the definition of SME’s has not had a lower limit for employees or their finances.

This rather generous new fee reduction policy has however been limited to applicants that have filed less than five EP-applications (including PCT regional phase applications at the EPO, i.e. Euro-PCT-applications) within the preceding five years. The period of five years is calculated from the filing date of the EP-application or the date of entry into regional phase at the EPO for Euro-PCT-applications. This means that for example universities and public research organisations, as well as actively patenting companies will rarely be eligible for these fee reductions.

In case there are several applicants, all applicants must be entitled to the fee reductions. The right to the reduction is to be fulfilled on the date of payment of the fee, for example when paying a renewal fee.

At the same time as the above changes, the EPO deletes some rarely used fees and increases some fees, although not all. Mainly the increase is of about 4 %, while the renewal fee for the fourth year increases for almost 30 %.

Some background and the decision of the Administrative Council can be found here: